- Home

- Tim Jarvis

Chasing Shackleton Page 2

Chasing Shackleton Read online

Page 2

Their bullishness was soon dampened, however, as they discovered the impossibility of pulling the lifeboats across the contorted surface of pack ice. The three lifeboats—the James Caird, Dudley Docker, and Stancomb Wills, named after the expedition’s sponsors—had been rescued from the Endurance and would be their only way home. But each boat weighed more than a tonne (a metric ton) and, despite being on sleds, was desperately heavy and cumbersome to pull. I can certainly attest to the difficulty of pulling a sled through the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean—like a building site with walls and piles of frozen rubble many meters high, over and through which you need to pick your way. A more demoralizing and confused surface would be difficult to imagine.

In light of the circumstances, Shackleton changed his plan and decided to set up Ocean Camp less than three kilometers from the wreck of the Endurance. The goal now was to hope they drifted northwest in the pack so that when it ultimately broke up, they would be free to complete the remainder of the journey at sea in the boats, sticking close to shore. It was a tense time as the wind appeared not to have read the script, sending them backward and out to sea as often as toward land. Meanwhile, Shackleton battled with severe sciatica and the men suffered in damp sleeping bags, the wood salvaged from the Endurance not insulating them sufficiently from the snow and ice beneath. They were also worried they would run out of food, given their rate of consumption. Just when any sane consideration of their circumstances would surely have resulted in feelings of utter hopelessness and despondency, Shackleton’s optimism again came to the fore. Such an ability to look favorably at one’s predicament, almost to the point of self-delusion in the face of the awful truth of one’s circumstances, is crucial to every polar expeditioner, especially given the enormity of the task one sets oneself in places where the chances of success are low and problems and doubts unrelenting. It was a skill over which Shackleton had complete mastery, but it was not to everyone’s liking. The Endurance’s first officer, Lionel Greenstreet, referred to it as “absolute foolishness,” summing up what quite a few of the men thought.

It was here at Ocean Camp that Shackleton got the expedition’s carpenter, Henry “Chippy” McNeish, to begin preparing the Caird and the other boats for a long sea journey. With extremely limited resources, McNeish managed to add thirty-five centimeters to the gunwales of the Caird using nails from the Endurance and filling the seams with lamp wick and the oil paints of Marston, the artist. This gave the Caird some seventy centimeters of freeboard, all of which would be needed for the journey ahead.

Despite Chippy McNeish’s excellent work, relations were not good between him and Shackleton. The carpenter, who feared the drift was carrying them out to sea, had vocally disagreed with Shackleton’s latest decision to begin marching again toward land. The rift between the two men would never heal, as Shackleton felt McNeish’s behavior was tantamount to mutiny. “I shall never forget him in this time of stress,” he lamented. In the end, ice conditions forced a rethink anyway and a move to stronger ice nearby and what they dubbed “Patience Camp.” Here, a more candid assessment of their dire food situation resulted in the need to shoot twenty-seven of their dogs that they could no longer afford to feed, Frank Wild reporting that it was the worst job he had ever had to do: “I have known many men I would rather shoot than the worst of the dogs.”

Man-hauling the boats: in a desperate bid to reach the open sea and be free of the ice, the crew tried to drag the boats by hand.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, SLIDES 22/39

Fear and uncertainty stalked the camp as the men drifted north, parallel with the peninsula and tantalizingly close to Paulet and Joinville islands, less than five kilometers to the west and the last islands before the end of land, the vastness of the Southern Ocean, and an even worse fate.

Over the course of the next week, the men were carried farther north out into the open ocean by the strong currents, their soccer-field-sized home rapidly disintegrating beneath them in the big ocean swell—a two-meter-thick leaf on a 2,000-meter-deep pond. Finally, a further crack in their floe forced their hand and they launched the boats on April 9, knowing that either Clarence or Elephant Island, the mountains of which had appeared on the horizon, was their last chance of survival. If they missed the islands, certain death at sea awaited. It was the austral autumn of 1916, the First World War raged on, and the crew of the Endurance were twenty-eight men in three small wooden lifeboats adrift in the roughest ocean in the world.

Their journey was a terrifying one. Initially it involved trying to follow leads in the shifting pack ice that dangerously opened and closed with a force that could crush the boats in an instant. Although terribly dangerous, at least the pack afforded protection from the open water that was far rougher without the dampening effect of the ice. Plus each night they could at least camp on a suitable floe—a better option than remaining on the open sea.

Based on the constantly changing winds, at one stage Shackleton opted to aim for King George Island to the west. Then the winds changed again, driving them depressingly back beyond Patience Camp. At this stage they had no drinking water left and the men were exhausted and understandably fearful of what might happen next. Temperatures were well below freezing, snow was falling, waves were crashing into the boats, and the Stancomb Wills, whose gunwales had not been raised, was awash with knee-deep, freezing seawater. Hypothermia was close at hand and the men were suffering from trench foot—an ailment not unlike frostbite—caused by the cold, damp, restricted conditions. In addition, a dangerous apathy was setting in, born in roughly equal parts of their being completely at the mercy of the elements and their utter exhaustion. Shackleton decided to head for Elephant Island, admitting privately that he “doubted if all the men would survive that night.” Elephant Island was deemed to be the better option largely because the winds they had would allow an attempt at Clarence if they missed it. If they missed Clarence Island, that would be it: there was no more land save South Georgia, an impossible 800 nautical miles to the northeast—an inhospitable dot in a very large ocean.

Shackleton approached the underbelly of Elephant Island in a howling gale, aiming for a broad bay some seventeen miles wide on its southeastern side that they could not see due to the “blackness of the gale and thick snow squalls,” according to Worsley. They approached cautiously until the wind yet again changed direction, blowing from the southwest, directly behind them, causing heavy, confused seas. Worsley, who was skippering the Dudley Docker, felt there was serious danger of capsizing. Finally, they managed to round Cape Valentine, the strength of the sea abating and the gale decreasing as they moved into the lee of the island, but it had been a desperately close run.

On Elephant Island, the end of an improbable journey for two lifeboats—but only the beginning for the James Caird.

From the Collection of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

Sealers named Elephant Island, or Sea Elephant Island, after the massive creatures that lived there, the only mammals that had managed to establish themselves on its inhospitable shores. Even the sealers and whalers themselves had been unable to do so due to its remoteness, rough weather, and absence of a sheltered anchorage. Every indentation of Elephant Island’s rugged coastline is steep glacial ice save for the dark rock cliffs that descend directly into an ocean of huge seas crashing unrelentingly at their base.

After their arrival, the mist cleared, as expedition photographer Frank Hurley’s description of Cape Valentine attests. “Such a wild and inhospitable coast I have never beheld,” he wrote, going on to describe “the vast headland, black and menacing, that rose from a seething surf 1,200 feet above our heads and so sheer as to have the appearance of overhanging.” All in all this meant that, other than representing terra firma, Cape Valentine was a very poor prospect for their ongoing survival. Their position on a narrow, shingle beach underneath overhanging cliffs meant it was a race between a big sea washing them away or snow, ice, and rocks cascadi

ng down on them from the cliffs above. They had to move immediately.

Frank Wild again took to the sea in the Dudley Docker to find a better camp, and chose the spot later named Point Wild by the men in his honor. The name could just as easily have been a description of the site itself—a shingle and rock spit extending perpendicular into the sea capped by large, rocky outcrops on the seaward side. Seas from both east and west battered it. The western side, meanwhile, was routinely choked with ice from the glacier only 200 meters away, major ice falls created enormous waves that on several occasions almost engulfed Shackleton’s puny camp on the shingle beach. The violent, contorted river of glacial ice prevented progress anywhere on foot to the south and west while 300-meter-high black cliffs did the same to the east.

Iron Men: Shackleton’s chosen few, clockwise from top left: Tom Crean, John Vincent, Chippy McNeish, Timothy McCarthy, and Frank Worsley.

(top right) Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge

(top left) Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, ON 26/5

(bottom right) Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, SLIDES 22/123

(bottom left) Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, SLIDES 22/121

All were relieved to have made it to this inhospitable, rocky outcrop, no one more so than Shackleton. But his relief was soon overshadowed by the knowledge that, on an island without a human population and seldom visited even by whalers, they would never be found. He knew, too, that only a thin veneer of morale remained among many of the men despite the joy and relief—initially at least—at having made it this far, and that neither morale nor men would likely survive the fast-approaching winter. It was April 1916, and with autumn upon them already, he knew that he would have to bring civilization to them, and waste no time in doing it.

The journey that followed unbelievably eclipsed what had gone before and was described by Sir Edmund Hillary as “the greatest survival journey of all time.” Shackleton and five of his most able men left Elephant Island on April 24 on an 800-nautical-mile voyage across the notoriously treacherous Southern Ocean in the largest of the three lifeboats, the James Caird.

Frank Worsley was skipper. The New Zealander was something of an eccentric, a risk taker and not a natural leader—in the authoritarian sense at least—but he was undoubtedly one of the most accomplished sailors of his time. Tom Crean was a tough Irishman from County Kerry and perhaps the strongest polar expeditioner of the heroic era. He was fiercely loyal to Shackleton and virtually begged to be included in the Caird team. His experience and resilience were invaluable: as a petty officer in the Royal Navy, Crean had already served under Scott on two of his Antarctic expeditions. Chippy McNeish, with whom Worsley in particular did not get on, was a rough Scot whom Shackleton described as “the only man I’m not dead certain of.” But his efforts to make the Caird more seaworthy were remarkable and, as it turns out, critical. One of the oldest men on the Endurance, McNeish had a rough, cantankerous manner that was problematic, and Shackleton undoubtedly chose him for the Caird crew as much to safeguard morale among those left behind on Elephant Island as for his respected skills as a sailor and shipwright. Similarly, Shackleton chose John Vincent, a hardened ex-naval North Sea trawlerman, because of his physical strength and sailing skill, but in no small part to remove him from Elephant Island due to his bullying ways. Timothy McCarthy, meanwhile, was perhaps the best and most efficient of the sailors, always cheerful under the most trying circumstances and described by Worsley as “the most irrepressible optimist I’ve ever met.” Having survived this great journey, he was tragically still claimed by the sea, dying as he did only three weeks after returning home on a navy ship that was lost with all hands during the Great War. It was McCarthy’s first day under enemy fire.

For seventeen days this tough group of men battled constant gales, terrible cold, and mountainous seas in their twenty-three-foot keel-less wooden boat, using only Worsley’s occasional sextant sightings from the boat’s pitching deck to navigate by. That they not only found South Georgia but also managed to land on this remote island is incredible. Their epic voyage and subsequent survival is a remarkable testament to both Shackleton’s leadership and the seamanship of Worsley, who saw the sun for only four sightings during the whole voyage in tumultuous seas.

Upon their arrival at South Georgia, following a hurricane that nearly finished them off, the six men clawed their way into King Haakon Bay, a spectacular fjord on the southwestern side of the island. There, Shackleton left Vincent and McNeish, who were too exhausted to continue, in the care of McCarthy. He, Worsley, and Crean then climbed over the unexplored, heavily glaciated mountains of South Georgia to reach Stromness whaling station on the other side. It was a thirty-five-kilometer journey that the world’s top mountaineers in the modern era have subsequently been unable to replicate in the way Shackleton did it.

Ultimately Shackleton was able to save all of his men—the three who remained on the other side of South Georgia and, with the help of the Chilean Navy, all twenty-two of the crew members who had been left stranded on Elephant Island. It was an epic triumph of endurance and leadership.

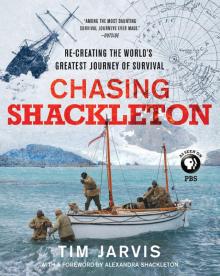

This boat journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia and the climb across the mountains to Stromness was what Zaz had been referring to when she asked me to lead a team to attempt “the double.” My unequivocal agreement meant I needed not only to build a replica Caird from scratch but also to assemble a team skilled and brave enough to attempt this with me.

So why did I do it? A simple answer was that I was honored to be asked by Shackleton’s granddaughter to undertake this journey and was inspired to want to do it as the greatest survival story of the heroic era of exploration. Despite my reprising the conversation her grandfather and Worsley had had in which Shackleton suggested he was “no small-boat sailor,” she remained unmoved and I am grateful to her for her confidence. In no small part, too, it felt like the logical conclusion of my bid to cross Antarctica in 1999, thwarted as it was by a fuel leak 1,800 kilometers into the crossing. I hadn’t been trapped in the pack ice as Shackleton had been, unable even to land on Antarctica, but I still had unfinished business in the Great White South. Perhaps the journey in the replica Caird and climbing across South Georgia would be a closing chapter for us both.

At a more philosophical level, I consider exploration to be the adventure of seeing whether or not you can achieve something, the thrill of trying, and the process of learning more about yourself and your surroundings that going on a journey to find out affords you, and I think this outlook is consistent with Shackleton’s. That we as individuals need to challenge ourselves to find out more about the world and our place in it is, I believe, as relevant a concept now as it was for Shackleton. As André Gide said so eloquently, “It is only in adventure that some people succeed in knowing themselves—in finding themselves.”

Certainly this love of exploration both literal and personal was a major driver for Shackleton, as undoubtedly was the desire to excel, with polar exploration being the means by which this could happen. As a middle-class, merchant-navy man of Anglo-Irish parentage (despite moving to England at the age of ten, his voice apparently retained traces of his Irish roots), he did not naturally fit easily into either Irish or English society, obsessed as they were in Edwardian times—and to an extent still are—with social standing. As the outsider—unlike Scott, who in every way represented the establishment—Shackleton defied pigeonholing and actively resisted it, displaying a healthy disregard for class and tradition. Polar expeditions offered him a way to transcend these boundaries while fueling his love of adventure—and not hurting his marriage prospects either.

Perhaps it was this refreshingly modern attitude that resonated so strongly in my own mind, as much as his extraordinary achievements. The more I discovered about Shackleton, the more I recognized, from his adaptability born of living in a number of different places and needing to fit in, his determination to follow projects through to completion and the energy

with which he did so, right down to the stubbornness and impatience he exhibited once he had decided upon a course of action. His intolerance of any negativity expressed by his men, along with his not being fazed by problems as long as a solution was suggested, were also familiar attitudes, not to mention his hunger for adventure and new experiences. In short, had we met over a few drinks, I think Shackleton and I would have had quite a few things to talk about and agree on.

And, of course, there were the many intriguing anecdotal details that made Shackleton such a compelling character and the story of his survival so remarkable. His powerful personal charm and charisma, which enabled him to talk as easily to Kaiser Wilhelm II as to the lowliest member of his crew and which won over financial backers for his expensive expeditions and gained him the unswerving loyalty of those who served under him (who affectionately called him “the Boss”), are the stuff of legend. Combine this with the failings he displayed both financially and personally and, for me, he became over time the most extraordinary and most “human” of all the heroic-era explorers. The invitation to retrace his journey was more than just an opportunity for adventure.

In the years since the achievements of Shackleton and his peers, there has been an ebb and flow in the way in which their exploits have been regarded. Mawson survived to old age, going on to achieve great things beyond his Antarctic feats, and is now finally beginning to get the recognition he deserves. Scott, once the hero who had paid the ultimate price by selflessly giving his life in the pursuit of his goal, has come to be seen by many as someone who went too far. Perhaps he was too readily prepared to sacrifice not only his life but also those of his men, and made serious mistakes along the way that contributed to their demise. Amundsen, who was seen as unfeeling and dispassionate with his routine butchering of his dogs and clinical way of operating on the ice, with time has revealed human failings. His poor judgment in initially leaving too early in his first bid for the South Pole meant his men barely escaped with their lives. One, Hjalmar Johansen, felt so betrayed he fell out with Amundsen and was dropped from the successful polar team. The shame he felt resulted in Johansen taking his own life.

Chasing Shackleton

Chasing Shackleton